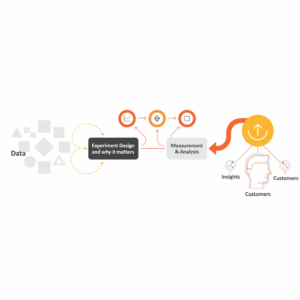

What is “experiment design” in CX and service transformation?

Leaders define experiment design as the structured plan that governs how a team runs a test to estimate cause and effect with confidence. The unit is the blueprint for randomization, controls, measurement, and analysis that turns ideas into evidence. In customer experience and service transformation, experiment design separates correlation from causation so executives can decide which journeys, scripts, and policies to scale. Proper design uses control groups, random assignment, and predefined outcomes to reduce bias and isolate the impact of a change on customers and the business.¹ This clarity helps cross-functional teams evaluate options objectively and prevents overconfidence in noisy metrics or seasonal trends. A sound design allows teams to compare like with like, quantify uncertainty, and communicate results in a format that supports accountable governance.²

Why does rigorous experiment design matter to enterprise outcomes?

Executives fund programs that win reliable returns, not anecdotes. Strong designs increase decision quality because they produce effect sizes with known error bounds and known risks of false alarms.³ Service organizations face interacting variables such as channel mix, agent behavior, and customer intent. An experiment built on random assignment and pre-registered hypotheses gives leaders a defensible path through this complexity.² In digital CX and contact centres, small lifts in conversion, containment, or handle time compound across high volumes. Robust designs detect these lifts at practical sample sizes and prevent teams from shipping regressions that look good in uncontrolled dashboards.³ When leaders require design discipline, they build a culture that values learning velocity over opinion velocity. The result is fewer costly rollbacks and faster scaling of features that truly help customers.³

How do strong designs reduce bias and noise?

Teams fight bias and noise by using randomization, controls, and blinding where feasible. Randomization balances unobserved factors across treatment and control so differences in outcomes are attributable to the intervention and not to confounders.¹ Control groups serve as the baseline to account for time trends, promotions, or traffic shifts outside the team’s control. Predefining primary outcomes and analysis windows protects against p-hacking and outcome switching.³ Sequential monitoring rules maintain valid inferences if teams look at data before the scheduled end.⁴ These guardrails reduce false positives, keep error rates under control, and ensure that measurement reflects the customer impact of the change rather than analyst enthusiasm.⁴

What are the essential components of an A/B test in CX?

Leaders specify the test unit, the randomization scheme, the primary metric, the minimal detectable effect, and the stopping rule. The test unit can be a session, a customer, an agent, or a location; the choice must align with how the change acts on behavior.³ The randomization scheme assigns units to treatment or control with balance and independence. The primary metric reflects the business goal, such as first contact resolution, conversion, NPS follow-up completion, or average handle time. Teams compute sample size using a power analysis that sets the probability of detecting a true effect of a chosen size at an acceptable error rate.⁵ Stopping rules define when to end the test and what to report. Together these elements create a plan that is auditable, repeatable, and tuned for decision utility.²

Where do CX metrics go wrong without good design?

Organizations mislead themselves when they ship features based on pre-post comparisons, overlapping campaigns, or uncontrolled pilots. Pre-post deltas confound the effect with seasonality and secular trends.² Concurrent experiments can interfere with each other when the same units receive multiple treatments.³ Peeking at interim results without valid sequential methods inflates false positives and encourages premature launches.⁴ Analysts also risk “metric shopping” by reporting only favorable outcomes after seeing the data.³ Good design anticipates these failure modes and neutralizes them with gating, isolation plans, and pre-registration.³ This discipline protects both customers and brand credibility by preventing launches that help a dashboard but harm the journey.

How do we choose metrics that reflect customer value?

Teams choose metrics that tie directly to customer value and business objectives, then guard them with quality checks. In service contexts, candidate metrics include first contact resolution, replies per conversation, containment rate, average handle time, and agent satisfaction. A balanced scorecard pairs a primary metric with guardrail metrics to detect trade-offs such as reduced handle time that damages resolution.³ Analysts validate metric sensitivity by simulating plausible changes and verifying that the metric would move detectably under the minimal effect of interest.³ Uplift-based targeting and heterogeneous effects analysis help teams understand which customers or segments benefit most, enabling targeted rollouts and reducing average harm.⁶ Clarity on metric definitions and audit trails for any changes ensure that results remain interpretable across cycles and leadership changes.²

How should we size, run, and stop CX experiments responsibly?

Leaders size experiments with power analysis to control Type I and Type II errors at preselected thresholds. Power analysis links sample size to the minimal detectable effect, the baseline rate, and the desired confidence.⁵ Teams run tests to completion under a published schedule or use always-valid methods that allow continuous monitoring without biasing error rates.⁴ During execution, analysts track exposure balance, event logging quality, and any violations of randomization such as agent overrides or routing quirks.² At stopping, teams compute intent-to-treat effects to preserve randomization, report confidence intervals, and document assumptions.³ Post-analysis examines heterogeneity and operational learnings for rollout. This cadence keeps governance crisp and accelerates responsible scaling of improvements that matter to customers.

What are the common threats in contact centres and service journeys?

Service tests encounter spillovers between agents and customers, noncompliance, and identity resolution challenges. Spillovers occur when treated agents influence control agents through coaching or shared queues.³ Noncompliance arises when agents deviate from scripts or when customers receive treatment through alternative channels. Analysts counter these threats with cluster randomization at the team or queue level, intent-to-treat analysis, and monitoring of treatment fidelity.³ Identity resolution issues occur when multiple identifiers map to the same person or when cookies fragment across devices. Sound identity and data foundations improve unit consistency and reduce measurement error. Strong instrumentation with event time stamps and immutable IDs strengthens auditability and supports trustworthy causal inference in operational environments.⁵

How do we compare experiment design to quasi-experiments and observational analysis?

Executives often balance randomized experiments with quasi-experiments when randomization is impractical. Randomized controlled trials remain the gold standard for causal identification because randomization balances unobserved confounders.¹ Quasi-experimental methods such as difference-in-differences or synthetic controls can provide credible estimates under explicit assumptions about parallel trends and structural stability.⁵ Observational causal inference uses models, matching, or instrumental variables to approximate the counterfactual but demands careful diagnostics and sensitivity analysis.⁷ In CX programs, leaders prefer randomized designs for core product or policy decisions and reserve quasi-experimental tools for contexts with strong governance and measurable assumptions.² This hierarchy keeps the bar high for changes that touch many customers.

What is the impact when organizations build an experiment-first culture?

Organizations that institutionalize experiment design increase learning velocity and reduce waste. Teams write concise test charters, maintain a shared registry of experiments, and require pre-commitment of metrics and analysis plans.³ Product, operations, and compliance collaborate on identity foundations and exposure rules to ensure data integrity and customer protection.² Leaders celebrate invalidated hypotheses because each well-run test closes uncertainty and prevents misguided investments.³ Over time, this culture produces compounding gains in conversion, containment, and satisfaction while reducing rework and customer friction.² The result is a portfolio where evidence guides scaling and customer outcomes improve predictably.

What are the next steps for leaders who want to start today?

Executives can start by naming a single owner for experiment quality, publishing a standard test plan template, and setting approval gates for randomization, metrics, and stopping rules.³ Teams can pilot one or two high-value A/B tests with clean units and clear metrics, then share results and learnings publicly.² Analytics can deploy a power and sample size calculator, implement event-level logging with stable identifiers, and set up sequential monitoring where needed.⁴ Training can focus on practical skills such as defining minimal detectable effect, writing hypotheses, and diagnosing exposure issues.² This simple operating model creates a repeatable pipeline from idea to decision, with customers at the centre.

FAQ

What is the definition of experiment design in customer experience?

Experiment design is the structured plan for randomization, controls, metrics, and analysis that estimates the causal impact of a change on customer and business outcomes.¹

Why should contact centre leaders prefer randomized A/B tests over before-and-after comparisons?

Randomized A/B tests reduce bias by balancing unobserved factors across treatment and control, while pre-post comparisons confound changes with seasonality and external trends.¹

Which metrics best reflect customer value in CX experiments?

Leaders select a primary outcome tied to customer value, such as first contact resolution or containment, and pair it with guardrails like handle time or satisfaction to detect harmful trade-offs.³

How do organizations size an A/B test correctly?

Teams use power analysis to connect sample size to baseline rates, minimal detectable effect, and acceptable error rates, ensuring tests are neither under-powered nor wasteful.⁵

What risks should executives watch for during live service experiments?

Key risks include interference across agents or queues, noncompliance with scripts, identity resolution errors, and invalid peeking at interim results without proper sequential methods.³

Who should own experiment quality in a transformation program?

Executives should appoint a single owner for design standards, pre-registration, exposure governance, and reporting, supported by analytics for power, logging, and monitoring.³

How can Customer Science support CX leaders on experiment design?

Customer Science helps leaders establish identity and data foundations, define metrics and guardrails, operationalize randomization, and implement governance that accelerates evidence-based scaling.²

Sources

Fisher, R. A. 1935. The Design of Experiments. Oliver & Boyd. Cambridge University Press page.

Kohavi, R., Tang, D., Xu, Y., & Zheng, A. 2020. Trustworthy Online Controlled Experiments: A Practical Guide to A/B Testing. Cambridge University Press. Book page.

Kohavi, R., Longbotham, R., Sommerfield, D., & Henne, R. M. 2009. “Controlled experiments on the web: survey and practical guide.” Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery. Microsoft Research PDF.

Johari, R., Pekelis, L., & Walsh, D. J. 2017. “Always Valid Inference: Bringing Sequential Analysis to A/B Testing.” arXiv e-prints. arXiv link.

Hernán, M. A., & Robins, J. M. 2020. Causal Inference: What If. Chapman & Hall/CRC. Online book.

Gutierrez, P., & Gérardy, J. Y. 2017. “Causal Inference and Uplift Modelling: A Review.” arXiv e-prints. arXiv link.

Miller, E. 2010. “How Not to Run an A/B Test.” Evan Miller Blog. Article.